What the Fed's interest rate cut means for the U.S. economy

As growth flags, the Fed moves in

The smartest insight and analysis, from all perspectives, rounded up from around the web:

The Federal Reserve cut its key interest rate this week to protect the "record-long economic expansion from slowing global growth," said Christopher Condon at Bloomberg. The quarter-point cut is a signal from the central bank that it hopes to get ahead of a potential slump. Economic growth slowed to 2.1 percent in the second quarter, falling a full basis point below the first-quarter number. Though a rate cut is what President Trump — who tweeted that the Fed "let us down" by rejecting a bigger cut — has called for, it's actually a sign that Trump's "supercharging of growth hasn't worked" as advertised, said Matthew Yglesias at Vox.com. For two years, Trump has promised to achieve a "sustainable 3 percent economic growth rate by slashing government regulations and business tax rates." That's looking like an illusion. Early estimates of 2018 growth seemed to show that Trump might have met the target in 2018, but the latest data have made the government revise the numbers downward to 2.5 percent. The economic expansion under Trump has been merely "fine" — as it was in the later part of the Obama presidency.

It's worrisome that the economy really "isn't behaving as expected," said Nick Timiraos at The Wall Street Journal. When the Fed began raising rates from near-zero after the financial crisis, economists' "models held that falling unemployment would eventually fuel rising inflation." That's not all bad; inflation can be "a sign of healthy growth across the economy." But in fact, even with interest rates still at historic lows, inflation has been well below the Fed's 2 percent target. And while relatively low unemployment should have pushed wages higher, wage growth has been lackluster. That has led Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell to argue the economy is really barely above lukewarm. "To call something hot," said Powell, "you have to see some heat." In fact, whatever heat there was is disappearing, said Karl Smith at Bloomberg. Business investment fell 0.6 percent in the last quarter, compared with a 4.4 percent increase in the first three months of 2019. Exports were also down 5.2 percent, widening a trade deficit burdened by the tariff war with China. "If President Donald Trump wants to improve conditions — both in the economy and for his re-election — then he might start by ending his trade war."

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Conservatives and liberals, markets and media — everybody is applauding the Fed for cutting rates, said Ruchir Sharma at The New York Times. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) want to print money to pay for ambitious social programs. Trump wants the Fed to cut interest rates to restore growth to 3 and 4 percent. In the U.S. and elsewhere, central banks are "making money ever cheaper and more plentiful to try to juice growth." Despite this, the U.S. economy "has grown at half the pace" of other post–World War II recoveries. All that cheap money has done little for the real economy; it's just powered a boom in corporate borrowing and "a record bull run in the financial markets." Now the Fed's prescription is more rate cuts — setting the stage for exactly the kind of "debt-fueled market collapse" that tanked the world economy in the first place.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

'Elevating Earth Day into a national holiday is not radical — it's practical'

'Elevating Earth Day into a national holiday is not radical — it's practical'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

UAW scores historic win in South at VW plant

UAW scores historic win in South at VW plantSpeed Read Volkswagen workers in Tennessee have voted to join the United Auto Workers union

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

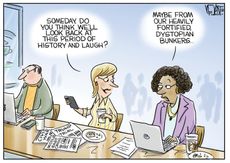

Today's political cartoons - April 22, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 22, 2024Cartoons Monday's cartoons - dystopian laughs, WNBA salaries, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion ban

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion banSpeed Read The law makes all abortions illegal in the state except to save the mother's life

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

Trump, billions richer, is selling Bibles

Trump, billions richer, is selling BiblesSpeed Read The former president is hawking a $60 "God Bless the USA Bible"

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitness

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitnessIn Depth Some critics argue Biden is too old to run again. Does the argument have merit?

By Grayson Quay Published

-

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?Today's Big Question Re-election of Republican frontrunner could threaten UK security, warns former head of secret service

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By The Week UK Published

-

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?Talking Point Top US diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize winner remembered as both foreign policy genius and war criminal

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Last updated

-

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'Why everyone's talking about Would-be president's sinister language is backed by an incendiary policy agenda, say commentators

By The Week UK Published

-

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?Today's Big Question Republican's re-election would be a 'nightmare' scenario for Europe, Ukraine and the West

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published