Aretha Franklin was power

Remembering the Queen of Soul

It is typical of our frivolity that a decade ago the Queen of Soul made news for wearing a hat. It was a perfectly sensible hat of a sort that millions of women in this country wear to church on Sundays and on other formal occasions, in this case the inauguration of our first black president. The way that legions of white observers fussed about her unremarkable fashion choice made me ashamed to be an American.

This is the only negative thing I have to say upon learning the sad news that Aretha Franklin has died at the age of 76.

Like those of so many of our greatest entertainers, her early life was itinerant. Before the age of 10 she had lived in Memphis, Buffalo, and Detroit, the city in which she died on Thursday and with which she will always be rightly associated. This is despite the fact that she was never signed to the record label that has become synonymous with black music of the era in which she performed.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

People capable of mistaking her for a Motown act prove they don't know anything about Aretha or about soul. The genius of the so-called Motown sound was that it distilled pop hit-making into a formula that could be replicated by anyone. Berry Gordy and associates stood for tight songwriting, snappy arrangements, tinselly emotion unobjectionable to the parents of white teenagers — all fine things in their way, but Aretha was interested in something else.

What was that thing? Simply put, autonomy, freedom, femaleness as opposed to femininity. There is, as Germaine Greer pointed out, often nothing especially feminine about being a woman. At Atlantic and, later, at Arista, Aretha was her own artist and, more important, her own woman.

The quality with which I shall always associate Aretha's voice is power. It is not a soft voice. It does not convey a great deal of pain, unlike that of many of her most esteemed predecessors or contemporaries. It rarely even evinces vulnerability. What it brings across, with its magnificent and unfailing energy — an energy that always avoids sounding compulsive on the one hand or manufactured on the other — is simply life. She saw a great deal of life, from New Bethel Baptist Church to New Haven, Connecticut, where she received an honorary doctorate from Yale in 2011. Doctor Franklin gave birth to two children before she was 15 years old and sang at the funeral of Martin Luther King, Jr., a friend since childhood; she knew what the world is and sang about it.

The other remarkable thing about her is that her instincts for choosing collaborators were nearly always unfailing. Duane Allman's slide leads on her cover of "The Weight" are so clear and forceful that we almost become convinced we are listening to a duet. She brought out the best in, among others, Quincy Jones, whose production of Hey Now (The Other Side of the Sky) in 1973 sounds as fresh and relevant as if it had been released last month, something that is not true even of his work with Michael Jackson.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

After a resurgence in 1985 with the platinum-selling Who's Zoomin' Who? her recording career declined. This retreat from the charts does not seem to have been accompanied by any correspondingly serious diminishment of her powers (though she often insisted otherwise). Her voice sounded subdued on her 1998 comeback, "A Rose is Still a Rose," but that seems to me more a result of Lauryn Hill's (now hopelessly dated) production than anything else. Anyone who watched her appearance on behalf of Carole King at the Kennedy Center Honors in 2015 knows what Aretha was capable of sounding like even very recently. It is not difficult to make sense of the tears in the eyes of those in the audience, including, it would appear, George Lucas.

In the coming days and weeks her hits — "I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Loved You)," "Chain of Fools," "Think," "Spanish Harlem," and, of course, "Respect" — will be replayed by millions and, one hopes, discovered by millions more. It is natural. Her hits are the things of which American culture is made, a hundred times more significant than any novel or play or poem of the last half century. But it is on the LPs where I think one can discover something of her real artistry: Soul '69, with a rendition of "Gentle on My Mind" that rivals even Glen Campbell's; This Girl's in Love With You (the haunting organ-driven "Let It Be" with its furious King Curtis solo was recorded from a demo version and issued months before the Beatles single); and Spirit in the Dark, with its extraordinary Franklin-penned originals, including the title track, and at least a dozen others.

In other words, we should listen to her music. Apart from praying for Aretha and her family, I can think of no other way to honor the memory of one who did so much for her people and her country.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

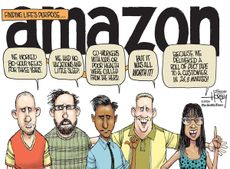

Today's political cartoons - April 19, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 19, 2024Cartoons Friday's cartoons - priority delivery, USPS on fire, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Israel hits Iran with retaliatory airstrike

Israel hits Iran with retaliatory airstrikeSpeed Read The attack comes after Iran's drone and missile barrage last weekend

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

How (and why) to have the inheritance talk with family sooner than later

How (and why) to have the inheritance talk with family sooner than laterThe Explainer The hard conversations aren't going to get any easier if you wait

By Becca Stanek, The Week US Published