America's politically homeless heartland

Why both parties ignore the Midwest at their own peril

The winds have turned yet again in the 2018 elections, and the Democrats are feeling their sails fill. Specifically, the congressional map is broadening, and it looks quite different from how the Democrats thought it might just a few short months ago. Back in 2017, many had anticipated a continuation of the trends of 2016, with the strongest pickup opportunities in relatively upscale suburbs that flipped from Mitt Romney to Hillary Clinton and hence had demonstrated a skepticism for an increasingly Trumpified GOP. Instead, most of the battleground turns out to be in Trump country — more specifically, in the part of the country that President Trump himself flipped to the GOP in 2016.

The biggest proportion of these seats is in the Midwest. Over 40 percent of the 26 seats rated as toss-ups by the Cook Political Report are in the Midwest, as are 30 percent of the larger group of 60 seats rated as most vulnerable to flip to the Democrats (current GOP seats rated Lean GOP to Likely Democrat). Far from having painted a previously blue region red, the Trump tide looks ready to recede, and a host of strong Democratic candidates are eager to plant their flag on that ground.

And yet, at the leadership level the Democrats have virtually no one that speaks with a Midwestern accent who could capitalize on these potential gains for something more lasting. Of the frequently-mentioned presidential contenders, the only officeholder who hails from the region is Ohio's Sherrod Brown; the only other prominent Midwestern contender is ... Oprah Winfrey. The great battle between the liberal establishment and the insurgent left is largely a coastal affair, pitting the likes of Nancy Pelosi (Calif.) and Andrew Cuomo (N.Y.) against Bernie Sanders acolytes like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (N.Y.), with hopefuls like Kamala Harris (Calif.), Cory Booker (N.J.) and Kirsten Gillibrand (N.Y.) vying for the support of both sides.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It was not always thus. For all his exoticism as the first African-American nominee, with a foreign-sounding name to boot, Barack Obama was a Midwesterner. His mother was born a Kansan, and when he settled down in his 20s he made his home — and found his spouse — in Chicago. The speech that first brought him to national attention was a weaponized version of a Midwestern emphasis on comity, and he broke through in his presidential bid in 2008 by winning the caucuses in neighboring Iowa.

His policy preferences also frequently had a Midwestern tinge. His relative skepticism of America's aggressive foreign policy — compared to his opponents in both the 2008 primaries and his two general election contests — has deep roots in the Midwest, and bonds him to other American presidents from the region like Ford, Eisenhower, and Harding. And in his first term he acted decisively to bail out the auto industry and cheered a massive expansion of fracking which gave an economic shot in the arm to states like Ohio and Pennsylvania.

So what happened? In 2010, the Democrats got shellacked in the region. They lost gubernatorial contests in Wisconsin, Iowa, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. They lost Senate contests in Pennsylvania, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin — four of the six Senate seats to flip in total. In the House of Representatives, fully one third of the seats the Democrats lost were in the region that runs from western Pennsylvania to eastern Kansas. While President Obama was able to win re-election with healthy margins across his home region, that success did not translate to the party as a whole.

And yet, apparently increasing Republican dominance masked profound disaffection below the surface — which is precisely why Donald Trump happened in the first place. Republicans have had no shortage of Midwestern hopefuls for the presidency, from Tim Pawlenty (Minn.) to Rick Santorum (Pa.), from Scott Walker (Wis.) to John Kasich (Ohio). Even when they've been popular enough back home to get themselves re-elected — even when they've polled extremely well in a hypothetical general election contest — they've proven unable to win on a national level.

Perhaps the reason is that party leadership required obeisance to an economic ideology that offers little or nothing to their states and is arguably culturally foreign to the region. Paul Ryan (Wis.), the retiring speaker of the House, famously claimed to have dreamed from his college days of privatizing Medicare; Michigan-born Mitt Romney, who chose Ryan as his running mate, famously opposed the auto bailout that saved his natal state from economic catastrophe. A real estate mogul and reality television star from New York was able to breach the blue wall in large part because he promised something very different: strengthened entitlements, rebuilt infrastructure, restored manufacturing, an America that was great because it took care of Americans first. Now that, apart from starting a trade war, he has failed to deliver, his popularity in the region is sagging badly, as is that of his party.

Democrats and Republicans alike have had every reason to prioritize the actual economic and social problems of the Midwest for quite some time, as no other region demonstrates more elasticity, more willingness to swing toward whichever party or candidate butters their bread more consistently. For both parties, the Midwest is an inviting target, but for neither is it a center of gravity. It's not where they develop their ideas, nor is it where they raise their money. It is not where their base lives, and in an era of base-mobilization politics that means appeals all too often take the form of trying to sort its population into those who are more like typical voters from the South, or from the coastal cities. Importing the country's deep national divisions hasn't notably helped the region, and it hasn't proved a recipe for lasting victory either.

The Midwest is not the economic dynamo that it was from the mid-19th to mid-20th centuries. But the slowest-growing region of the country still accounts for over 20 percent of America's population and over 20 percent of its economic output. And if it has struggled the most to keep pace with the changes that have swept much of the rest of the nation, that is all the more reason for it to be a particular focus of politics. The fact that Democrats have too often preferred to run on “be more like California” while Republicans have preferred to run on “be more like Texas” bespeaks both a profound lack of imagination, even a lack of ... diversity.

Hopefully, if November gives the Democrats the opportunity to change that, they seize it.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

UAW scores historic win in South at VW plant

UAW scores historic win in South at VW plantSpeed Read Volkswagen workers in Tennessee have voted to join the United Auto Workers union

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

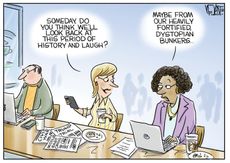

Today's political cartoons - April 22, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 22, 2024Cartoons Monday's cartoons - dystopian laughs, WNBA salaries, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Ukraine cheers House approval of military aid

Ukraine cheers House approval of military aidSpeed Read Following a lengthy struggle, the House has approved $95 billion in aid for Ukraine and Israel

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion ban

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion banSpeed Read The law makes all abortions illegal in the state except to save the mother's life

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

Trump, billions richer, is selling Bibles

Trump, billions richer, is selling BiblesSpeed Read The former president is hawking a $60 "God Bless the USA Bible"

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitness

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitnessIn Depth Some critics argue Biden is too old to run again. Does the argument have merit?

By Grayson Quay Published

-

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?Today's Big Question Re-election of Republican frontrunner could threaten UK security, warns former head of secret service

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By The Week UK Published

-

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?Talking Point Top US diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize winner remembered as both foreign policy genius and war criminal

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Last updated

-

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'Why everyone's talking about Would-be president's sinister language is backed by an incendiary policy agenda, say commentators

By The Week UK Published

-

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?Today's Big Question Republican's re-election would be a 'nightmare' scenario for Europe, Ukraine and the West

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published